From a Local: The Complete Guide to NYC’s Subway System

New York City is home to the most extensive mass transit system in the world, with 472 subway stations currently operating.

It’s also among the oldest and the busiest, which comes with some downsides that visitors may not anticipate. Still, if you want an authentic experience of the city, you cannot confine yourself to Lyft cars, tour buses, and hansom cabs. Your visit is not complete until you have ventured into the fetid nethers of New York’s subway tunnels. With this guide, you should survive your excursion with no (visible) trauma.

The Basics

Flickr user paulmmay

When visiting New York, you can use the subway to ride to and from all four boroughs—Brooklyn, Queens, Manhattan, the Bronx, and not Staten Island (it’s not a real borough, so you have to take the ferry). You can cross the Manhattan Bridge on the B, D, N, or Q trains to get a spectacular view of the skyline, or take more than a dozen lines for an ear-popping ride under the Hudson river. Google Maps will tell you how to get around (as long as there aren’t any of the frequent service issues…) and hopefully help you figure out if you need a local train that stops at every station or an express train that goes to only the busiest stops. Subway maps are usually posted in train cars and on the platforms, and if you need it, there’s even cell service in the stations now.

If you’re lucky, you might also end up in one of the updated stations that provide semi-reliable train arrival times, and you might get to ride one of the modern trains with futuristic features like audible station announcements—the upgrades are wildly inconsistent, and there are still trains from the 1960s operating. But to ride the subway at all (without being tackled by overzealous cops), the first thing you’re going to need is a MetroCard. It’s a flimsy bit of yellow plastic with a magnetic strip, sold out of machines in every subway station. It will cost you $1 a pop, plus whatever amount you want to spend on trips—one trip currently costs $2.75, but that price seems to go up every 12 hours or so.

If you’re planning to use it extensively, you might want to make your card unlimited, which will run you $33 for a week, or $127 for a month. Otherwise, you can put as much money as you think you’ll use and refill it as needed using the same machine that dispenses them. If you only have the stomach to take a single trip, you can buy a single ride card for $3. And if the machine is too daunting (or a line of locals forms while you’re trying to figure it out), many bodegas—AKA “delis”—also sell MetroCards.

One of the beauties of these MetroCards is that they also work with a number of other modes of transport, including the PATH trains to New Jersey, the tram to Roosevelt Island, the AirTrain to JFK. Most importantly, a swipe includes a two-hour window for a free transfer to or from a standard NYC bus, so you really can get just about anywhere with one swipe (though obviously not Staten Island, the non-borough).

The Buskers

What’s even more impressive is the amount you can do without having to leave the subway system. Along with the variety of stores, restaurants, florists, and newsstands, there is enough public art to fill a dozen galleries and a thriving live music scene. Unlike the carts full of churros—one for a dollar, three for two—New York’s buskers are legally allowed to share their talents without a license in subway stations and on the platform, and a great many of them are immensely talented. The larger and busier stations are particularly solid venues. The mariachi bands, barbershop singers, and dance crews who roam the trains themselves are somewhat less sanctioned. You don’t have to throw them a dollar if you don’t feel like it, but there’s no need to be a narc about it.

The Smell

Improv Everywhere

There’s a common misconception that the entire NYC subway system smells of stale urine. This is far from the case. Each station has its own smell—from musty basement to stagnant puddle water to sulfuric stalactites dripping from the ceiling. There are even open-air stations that smell of trees, diesel fumes, and putrefying garbage juice. Mixed in with these smells, there is often a healthy dose of stale urine, but it is hardly the sole, or even the predominant, scent.

That said, if a crowded train rolls into the station with one empty car, an overpowering stench is the best possible outcome of stepping into that car. Like most of the US, New York does not provide adequate housing for people with mental illnesses, drug addictions, or just nowhere else to go. Unlike most of the US, rent in New York costs more than the black market value of your organs, so there are a lot of homeless people who end up living their lives in the subway system, and sometimes making it smell terrible. So just choose another car.

Etiquette

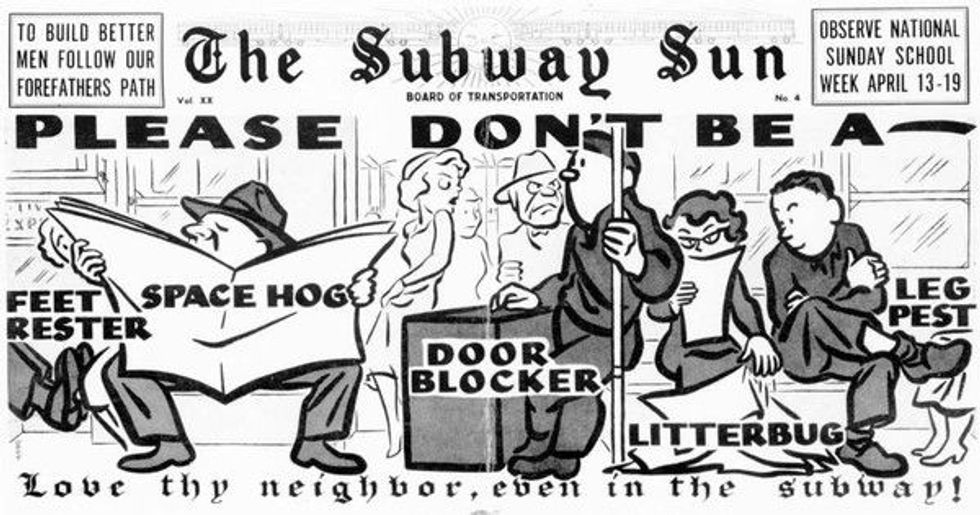

This is the most important part of using the subway. New Yorkers have a reputation for being rude, but that’s not entirely accurate. The reality is that New Yorkers are shockingly considerate of one another. With some notable exceptions, most of us do our best not to inconvenience or inflict stress on any of the thousands of strangers we encounter in a given day, and we often have little patience for people who don’t make the same effort. Our apparent indifference to the world around us can come across as cold, but we ignore one another as a courtesy—living so much of your life surrounded by strangers is a lot less stressful with the assurance that you aren’t constantly being observed and scrutinized. It provides a form of privacy and solitude, even in public.

So if you need some help navigating the subway, don’t let the lack of eye contact dissuade you from asking for help. If we have the time to help, most of us will. But please understand that your tourism playground exists in the same place where we’re trying to go about our daily lives. Our version of road rage is giving a nasty look to a slow tourist, so please do your best not to inconvenience us. That means letting people off the train before you try to get on, not taking up more room than you have to, and being aware of the people around you when they’re trying to move through the confined space of a train car or a subway platform.

- 14th street

- andy byford

- bedford avenue

- brooklyn

- buskers

- city subway

- east river

- east side

- east village

- eighth avenue

- governor's island tram

- hurricane sandy

- imrpov everywhere

- jfk airtrain

- manhattan

- metrocard

- metrocard price

- metropolitan transportation authority

- new york city

- new yorkers rude

- nights and weekends

- nyc

- nyc busking

- nyc homeless

- nyc subway

- nyc subway cost

- path train

- queens

- rapid transit system

- roosevelt isalnd tram

- roosevelt island

- staten island

- staten island ferry

- subway etiquette

- subway line

- subway map

- subway station

- subway system

- the bronx

- united states

- york city

- york city transit